Why should humans be the only species who use wearables to track their physical activity? Keeping that in mind, scientists have turned a crab into their test subject for a lightweight wearable. The crab was fitted with a sensor capable of tracking its movements deep in the ocean.

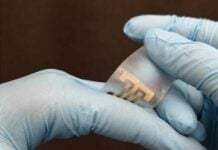

Dubbed “Marine Skin,” the wearable can be attached to the outer shell or skin of an animal. When in water, the sensor weighs about as much as a paper clip.

All of that means the lightweight skin could be worn by a wide variety of large and small marine animals living in the ocean, such as whales, sharks, and dolphins without disrupting their bodies or behavior underwater.

Read more Animal Dermatology Group Announces Scientific Publication Validating Wearables for Dogs

The tag was developed at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia and the research team aims to have it on as many as 200 different marine species by the summer of 2019.

These new marine skin tags are non-invasive; older forms of tags used invasive methods for attaching to the animals. In the 1930s, scientists used shotguns to shoot stainless tubes into whales. The tubes bore an identification number and promise of reward if returned. However, people would kill the whale and process it for blubber and then return the tube to collect reward. There are sophisticated tracking methods available now, but researchers often still rely on darting or implanting to fit the tags on animals.

Muhammad Mustafa Hussain, a professor of electrical engineering at KAUST, and his colleagues – working in collaboration with scientists at the Red Sea Research Center – aimed to meet the current standard for marine animal tagging in terms of non-invasiveness, weight, operational lifetime, and speed of operation.

“I realized we could help marine species by developing comfortable and convenient wearables for them,” said Professor Hussain.

Read more MC10 Receives its First FDA Approval for the BioStamp nPoint System

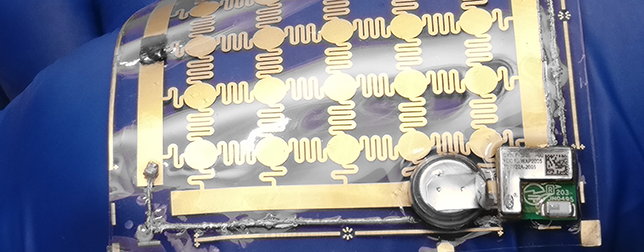

For their first swimming and driving test the researchers used a blue swimmer crab captured on the east coast of the Red Sea. The researchers fitted the tags with a small coin battery that can last up to a year. The prototype tag continuously tracked depth, seawater salinity and temperature. The trial suggested a battery life of 5 months without any optimization or changes made to data logging frequency.

Prof. Hussain and his team primarily used copper, tungsten, and aluminum in the electronic components and a common silicone for the main body of the skin. Material and processing costs for the wearable system are under $12 per unit; much less expensive than conventional marine tags.

One limitation is that the current prototype relies on a Bluetooth connection to a smartphone to transfer data. A second-generation sensor aims to transmit data wirelessly when the animal chooses to surface.

The study will be published in an upcoming issue of the journal Flexible Electronics.