Although sensors and wearable devices are getting smaller with each passing year, they still lack comfortability for the wearer. These devices need bulky batteries and other power sources to run. Now, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have developed sensors that can be powered by the wearer’s skin.

Related Exeter Researchers Develop Self-Powered Graphene-Based Wearable Sensors for Monitoring Vital Signs

“We’re using the human skin, which is composed of mostly water, as a conductor,” said Sunghoon Ivan Lee, a UMass Amherst researcher and assistant professor of computer science. “But human skin is one big chunk of conductive material, so there’s no distinction between the signal wire and the ground wire. So, we’re using the skin as a signal wire, and air as the ground.”

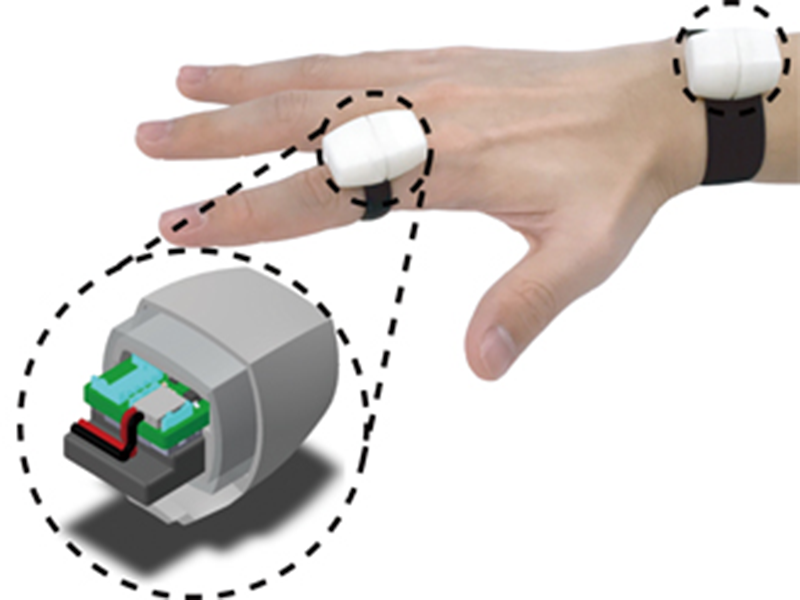

The self-powered sensors can be ultra-miniaturized and ergonomically designed for placement on small areas of the body, like a finger, an ear or even a tooth, reports UMass.

It’s a technological innovation unreachable with conventional in-device batteries. Which is why Lee and his team believe their research can lay the groundwork to transform existing architectures and spawn a new generation of on-body sensors.

“We’re working on a process that shrinks the size of devices so they can be placed on small parts of the body,” Lee said. “And because you don’t have to change batteries, there’s a variety of ways in which wearable sensors can be improved and expanded.”

Originally, the team started their research when they decided to understand how stroke survivors use their limbs. “If we could put a sensor on the finger, we could obtain clinically relevant information on impairment level,” Lee said. However, there was a small problem. The sensors were too bulky, and the batteries took up too much space.

Related Carnegie Mellon Researchers Develop Flexible Wearable Patch That Sticks to the Skin Like a Band-Aid

So, they started looking for ways to make the sensors smaller, lighter, more pliable and more energy-efficient. They found their answer in the natural conductive properties of skin.

While this new sensor is limited to usages on wrist and finger, other applications of the technology could lead to small wearable sensors placed within a person’s tooth or the ear, Lee said. Dentists could get a better understanding of the pressure or moisture levels of lost teeth. The ear sensor, on the other hand, could carry signals relating to muscle, eye and brain activities.