Engineers from Stanford University have developed a new calorie burn measurement system that is small, inexpensive and accurate. Also, people can make it themselves. Whereas smartwatches and smartphones tend to be off by about 40 to 80 percent when it comes to counting calories burned during an activity, this system averages 13 percent error.

“We built a compact system that we evaluated with a diverse group of participants to represent the U.S. population and found that it does very well, with about one third the error of smartwatches,” said Patrick Slade, a graduate student in mechanical engineering at Stanford who is lead author of a paper about this work, published in Nature Communications.

A crucial piece of this research was understanding a basic shortcoming of other wearable calorie counters: that they rely on wrist motion or heart rate, even though neither is especially indicative of energy expenditure. (Consider how a cup of coffee can increase heart rate.) The researchers hypothesized that leg motion would be more telling – and their experiments confirmed that idea.

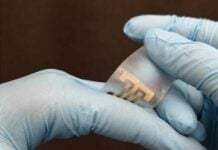

There are laboratory-grade systems that can accurately estimate how much energy a person burns during physical activity, but they involve bulky, uncomfortable equipment and can be expensive. This new wearable system only requires two small sensors on the leg, a battery and a portable microcontroller (a small computer), and costs about $100 to make. The list of components and code for making the system are both available, writes Taylor Kubota in Stanford News.

“This is a big advance because, up till now, it takes two to six minutes and a gas mask to accurately estimate how much energy a person is burning,” said Scott Delp, director of the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance at Stanford and the James H. Clark Professor in the School of Engineering, who is co-author of the paper. “With Patrick’s new tool, we can estimate how much energy is burned with each step as an Olympic athlete races toward the finish line to get a measure of what is fueling their peak performance. We can also compute the energy spent by a patient recovering from cardiac surgery to better manage their exercise.”

Looking to the legs

How people burn calories is complicated, but the researchers had a hunch that sensors on the legs would be a simple way to gain insight into this process.

The system the researchers designed consists of two small sensors – one on the thigh and one on the shank of one leg – run by a microcontroller on the hip, which could easily be replaced by a smartphone. These sensors are called “inertial measurement units” and measure the acceleration and rotation of the leg as it’s moving. They are purposely lightweight, portable and low cost so that they could be easily integrated in different forms, including clothing, such as smart pants.

To test the system against similar technologies, the researchers had study participants wear it while also wearing two smartwatches and a heart rate monitor. With all of these sensors attached, participants performed a variety of activities, including various speeds of walking, running, biking, stair climbing and transitioning between walking and running. When all of the wearables were compared to the calorie burn measurements captured by a laboratory-grade system, the researchers found that their leg-based system was the most accurate.

By further testing the system on over a dozen participants across a range of ages and weights, the researchers gathered a wealth of data that Slade used to further refine the machine learning model that calculates the calorie burn estimates.

Read more Flexible Cable Based Capacitors Support Energy Harvesting for Wearables

“A lot of the steps that you take every day happen in short bouts of 20 seconds or less,” said Slade, who mentioned doing chores as one example of short-burst activity that often gets overlooked. “Being able to capture these brief activities or dynamic changes between activities is really challenging and no other system can currently do that.”

An open design

Simplicity and affordability were important to this team, as was making the design openly available, because they hope this technology can support people in understanding and looking after their health.

“We’re open-sourcing everything in the hopes that people will take it and run with it and make products that can improve the lives of the public,” said Mykel Kochenderfer, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford who is a co-author of the paper.