At a time when 700 million adults and children worldwide are obese, and clinicians are fighting on the front lines of the obesity epidemic, researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison have invented an implantable battery-free device that could offer a promising solution to this menace.

Related Study: Weight loss wearables most effective alongside intradisciplinary approach

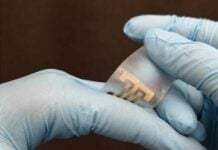

The tiny weight-loss implant is only about a centimeter across, stimulates the vagus nerve, and in turn the brain. In laboratory testing, the devices helped rats shed almost 40% of their body weight.

“The pulses correlate with the stomach’s motions, enhancing a natural response to help control food intake,” says Xudong Wang, a UW–Madison professor of materials science and engineering.

Gastric bypass surgery permanently alters the capacity of the stomach, but the effects of the new device can be reversed. When the researchers removed the devices from the rats after 12 weeks, the rodents resumed their regular eating patterns and they gained back the weight they lost, reports College of Engineering, UW-Madison.

This new device is easy to use and has several advantages over an existing device that works the same way. The existing device, called “Maestro,” is FDA-approved and uses high-frequency zaps to the vagus nerve to close all communication between the brain and the stomach. It requires a complicated control unit and bulky batteries that needs frequent charging.

“One potential advantage of the new device over existing vagus nerve stimulators is that it does not require external battery charging, which is a significant advantage when you consider the inconvenience that patients experience when having to charge a battery multiple times a week for an hour or so,” says Wang.

Related This Wearable Helps You Lose Weight by Analyzing Your Breath

The new device is battery-free, contains no electronics, and no complicated wiring. It relies instead on the undulations of the stomach walls to power its internal generators. That means the device only stimulates the vagus nerve when the stomach moves.

“It’s automatically responsive to our body function, producing stimulation when needed,” says Wang. “Our body knows best.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.