It is a well-known fact that UV exposure causes skin cancer. Skin Cancer Foundation reports that this menacing condition is on the rise. Can technology help prevent skin cancer?

In the past few years, we’ve seen a wave of UV-detection wearables, apps, and stickers designed to alert users to dangerous levels of sun exposure entering the market, reports Popular Science.

“Personal UV detection [devices] are finally being marketed to consumers,” says Elke Hacker, a researcher at the Improving Health Outcomes for People, part of Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia. She and other experts say that if these devices can accurately measure UV, they could have a big impact. But, the question is, ‘How effective are they?’

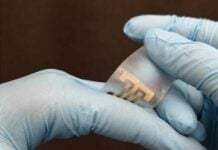

Most UV detecting wearables on the market today are designed to be worn around the wrist, clip onto clothes, and some can be stuck on your nail.

As part of her research, Hacker is responsible for testing UV wearables and other technology that could improve the health of Australians, who have high rates of skin cancer.

Most of these wearables use a dosimeter, a device that measures exposure to ionizing radiation to calculate UV exposure. Ionizing radiation is a type that’s at a high enough radiation level that it can physically remove an electron from an atom. If it reaches human skin cells, it can damage DNA and make the skin cancer risk higher. UVA and UVB are both ionizing, but UVB is far more ionizing.

The data is then wirelessly transmitted to an app, where users are asked about their skin type and if they have skin diseases. Both of these factors change how much sun you can get.

However, not all these devices measure real-time UV exposure. Some, like L’Oreal’s UV Patch, the Microsoft Band and Band 2, and Sunsprite, detect UV exposure by spotting visible light and then estimating the amount of UV based on that. Jonathan Zippin, an Assoc. Prof. of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medical Center in NY says, while this technique may give you an estimate of UV exposure, it’s not especially effective because it can’t precisely differentiate between UVA and UVB rays.

Dermatologist Lauren Eckert Ploch warns against relying on the devices to determine this amount of time. “I do not think that a UV dose sensor is helpful, as even minor doses of UV radiation are harmful to our skin. There’s no true ‘safe’ dose when we’re referring to UV radiation.”

Read more Stay Safe in the Sun: Smart Wearables to Monitor UV Radiation

But John Rogers, a materials scientist at Northwestern University who developed UV Sense, says doctors have established a baseline, contingent on skin color, for the amount of time before a sunburn occurs: About 10 minutes for a person with red hair and fair skin in Brisbane and longer the darker a person’s skin is, says Queensland’s Hacker. Though, Hacker and Rogers say, that burn-free time doesn’t keep a person free from UV damage.

So, should you buy one of these?

Zippin compares these UV sensors to at-home blood pressure monitors or blood glucose monitors, which can serve as a guide to people who worry about their UV exposure.

Especially, people who already have skin cancer or a condition aggravated by sun exposure may want a more precise method of calculating their daily activities, Zippin says. “For a lot of people, [UV exposure] is hard to wrap their head around,” he says. “And because sunlight isn’t easily measured, it’s a little hard for people to figure out how much sun is too much.”

Finally, we can do that with these devices, Zippin says. But before recommending them to his parents, he’s waiting on the results of the research that confirms they lower the risk of skin cancer.

Yet, Hacker is optimistic about the idea that technology can enhance the way we think about sun exposure. “We all want to go outdoors and enjoy the sun,” she says. We just need to do it safely.